Governing Our Trains: Unpacking the New Rail Funding Framework

- Emily Chen and Gan Xin Chen

- Mar 12

- 9 min read

In this Explainer, find out...

Why was the New Rail Financing Framework (NRFF) adopted?

How does the NRFF work and what are the key principles behind it?

What are the strengths and drawbacks of the NRFF?

Introduction

Singapore’s Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) system is a story of vision and resilience. In the 1980s, debates over whether to build a rail network or expand the bus system divided opinions. The MRT’s high capital costs sparked concerns, and even experts questioned its necessity. Yet, the rail option prevailed as buses alone could not meet the needs of a growing population.

Over the years, the MRT system has not only transformed how people travel, but it also shaped how public transport is planned and governed. The New Rail Financing Framework (NRFF), introduced in 2010, is the latest chapter in this ongoing effort to balance efficiency, sustainability, and the public good.

In this Policy Explainer, we begin by first painting the historical context within which the MRT and its governing models have developed. Afterwards, we explain what the NRFF is, and finally conclude by discussing the pros and cons of the NRFF.

So You Want Trains?

The Beginnings of the MRT System

While we sometimes take for granted that a mere 30-minute train ride connects Woodlands and Orchard today, much of our train system’s history was met with opposition due to its high capital costs.

For instance, although a 1981 Comprehensive Traffic Study decisively concluded that an MRT system would best complement the bus network, its high capital cost invited much objection. This caused the “Great MRT Debate” to ensue, with accredited international specialists even concluding that an expansion of the bus network was preferred.

However, the rail-based option prevailed. Though more expensive, it was assessed that a public transport system that relied solely on buses would be insufficient to meet the future needs of Singaporeans as the population grew. Hence, the construction of Singapore's first MRT line began in 1983.

Mounting Financing Challenges

Over time, Singapore’s MRT system continued to expand rapidly. However, this growth came with challenges.

By 2010, the system’s aging infrastructure and rising passenger load led to growing concerns about reliability. In the same year, two major breakdowns occurred on the North-South and East-West Lines (NSL and EWL), both managed by Singapore Mass Rapid Transit Corporation (SMRT). The disruptions left thousands of commuters stranded during peak hours, sparking public outrage. An independent Committee of Inquiry found that SMRT had failed to invest adequately in preventive maintenance. The company had prioritised cost-cutting, leading to system-wide weaknesses. This exposed a key problem — private operators, driven by profit motives, were not always incentivised to make costly but necessary long-term investments.

Despite promises of improvements, another major breakdown occurred in 2015 on the NSL and EWL, affecting over 250,000 commuters. It was one of the worst MRT disruptions in Singapore’s history. The incident reinforced concerns that private operators could not balance financial sustainability with service reliability on their own. The Government recognised that a new approach was needed — one that would allow for better oversight and long-term infrastructure planning.

A New Financing Model

Thus, the New Rail Financing Framework (NRFF) was introduced in 2010, with the Downtown Line (operated by SBS Transit) being the first to adopt it in 2011. After four years of discussions, the Government reached an agreement in 2016 to place SMRT’s lines (NSL, EWL, Circle Line, and Bukit Panjang LRT) under the new model. By 2018, the remaining SBS-operated lines (North-East Line and the LRTs in Sengkang and Punggol) followed suit.

The shift to NRFF could be seen as a response to the breakdowns. Under the NRFF, the Government took ownership of rail assets. This ensured that long-term investments in infrastructure and maintenance would no longer be constrained by private operators’ financial concerns. This hybrid model struck a balance between government oversight and private sector efficiency, helping to improve the MRT system’s long-term reliability.

Mechanics Of The NRFF

Three Versions

Since its implementation, the NRFF has gone through multiple iterations. In particular, three versions of this new financing model have been developed and refined over the years.

Under Version One of the NRFF adopted in 2011, the public transport operator collects the fare revenue paid by commuters. It also pays the Government a license charge for using operating assets like trains and signalling systems. Version One of the NRFF, however, had one significant drawback: it put a substantial financial risk on train operators as there were no mitigation measures in place to soften the blow should ridership fall. This was because train operators had to pay a fixed license charge, regardless of the number of riders. Hence, if train ridership was lower than expected, train operators would have to suffer the financial loss.

As such, Version Two of the NRFF was conceptualised to plug this gap. More mechanisms were put in place to address the potential fall in train ridership. For example, the Land Transport Authority (LTA) pledged to absorb some of the financial losses in times of lower ridership. Reciprocally, should the ridership be higher than expected, the rail operator would pay more for the license charge that will be diverted into the Railway Sinking Fund — a fund used for the renewal of operating assets.

Further efforts to support the rail industry later led to the development of Version Three of the NRFF. Under this model, financial risk is further taken on by the Government as it collects all fare revenue — thus effectively taking on all revenue risk when the initial ridership is unstable. In return, the Government grants a fixed fee to the operator to run the rail line. As Associate Professor Walter Theseira explains, Version Three of the NRFF is more suitable for new railway lines with unstable ridership numbers. Hence, not all railway lines would have to transition into this iteration of the NRFF.

With such refinements across the three versions of the NRFF, better allocation of roles between the private and public sectors has been achieved. Under the framework, the former focuses on providing better services for commuters, while the latter bears the heavy financial burden. Two characteristics of the NRFF, in particular, merit deeper analysis.

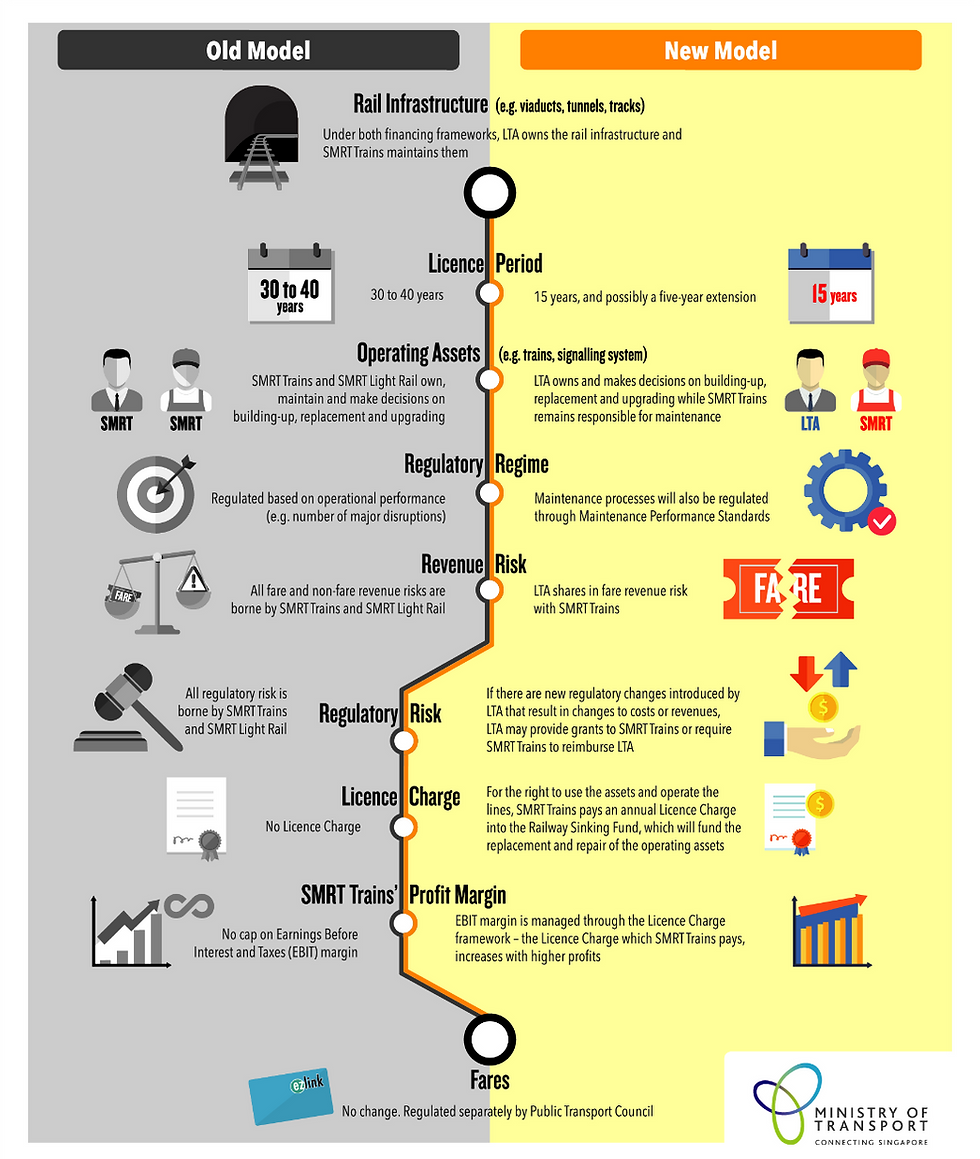

Public-Private Cooperation

First, the NRFF introduces a framework of public-private cooperation. This allows for clearer differentiation of roles between the public and private sectors. Following the acquisition of over 60,000 operating assets from SMRT in 2016, LTA now holds ownership over all rail assets and will be making decisions on the “building up, replacement and upgrading” of the train system moving forward. With the public sector taking on the heavy capital expenditure, the private sector can focus on ensuring the reliability of rail services for commuters instead. This includes the maintenance of train networks, which remain under the purview of the private operators.

Shortening Operating Licenses

Second, as part of Version Three of the NRFF, operating licenses will also be shortened to 15 years, from the previous 30 to 40 years. Operating licenses are licenses that allow rail companies to operate the railway services. This allows LTA to re-tender the operation of rail lines more. In turn, this prevents the domination of the railway industry by one single provider (thereby creating a monopoly). Such monopolisation is possible given the higher operational costs that lead to significant barriers to entry. In turn, barriers to entry make it difficult for new operators to enter the market for railway services. Therefore, if not regulated over time, monopolies in the railway industry can lead to increasing costs as operators lose the incentive to reduce costs.

Now, with the constant need to re-tender, private operators must continuously find ways to cut their operating costs to be able to secure fresh tenders. Thus, this ensures that the rail industry remains competitive, which in turn, encourages innovation across its various operators.

Apart from increasing the competitiveness of the rail industry, the shortening of operating licenses also gives LTA more flexibility in fine-tuning new requirements with each iteration of licenses issued.

What's Good About The NRFF?

Social Benefits

As mentioned, the NRFF was designed to address the high financial costs of building, maintaining, and upgrading MRT infrastructure. Fixing track faults or updating signalling systems, for example, needs substantial funding. Private companies may not always have the financial capacity or incentive to make these long-term investments, which can lead to service disruptions and declining reliability.

Beyond its role as a transport system, the MRT also provides broader benefits to society (positive externalities). A well-functioning rail network encourages more people to use public transport instead of driving, which helps reduce road congestion and air pollution. However, private operators, driven by financial considerations, may not invest enough to maximise these benefits. This is why the Government implemented the NRFF. By taking ownership of rail assets, it ensures that a critical infrastructure like the public rail network receives the necessary funding and long-term planning. In turn, this creates a more sustainable and efficient public transport system for Singapore.

Cap-and-Collar

Furthermore, the NRFF model of rail financing introduces a “cap-and-collar” approach. This entails operators paying less in license charge when the actual revenue falls below the projected revenue stipulated by the LTA (“revenue collar”). In a similar vein, operators will pay the LTA more in license charge when the converse occurs (“revenue cap”).

As explained by the LTA, the cap-and-collar approach helps to reduce pressure for private operators to operate on a profit, which can in turn allow them to divert their attention towards improving the quality and reliability of the rail services.

Excessive Optimism?

Possible Drawbacks of the NRFF

However, a cap-and-collar approach risks disincentivising innovation as private operators prioritise short-term profit-maximisation instead. Given that there is a “cap” on the profit rail operators can make, there is less incentive to invest in long-term innovations. Instead, cost-cutting measures that maximise short-term returns without exceeding the profit ceiling becomes more attractive instead.

By extension, the shortening of operating licenses means that private operators would have less time to fine-tune best practices to maximise efficiency. In turn, this may result in higher operating costs in the long run instead.

An Alternative to the NRFF: Nationalisation?

In London, New York, and Tokyo, public transport systems are completely nationalised. Nationalisation entails the government owning and operating the entire transit system. This means that the government is responsible for funding, managing, and maintaining operations. Proponents of such full-scale nationalisation argue that the government is in the best position to oversee and govern the public interest, ensuring that the transit system maximises societal welfare.

Contrastingly, the current NRFF differs from nationalisation because it is a hybrid model. Instead of the Government owning and running the entire MRT system directly, it only owns the infrastructure (e.g. tracks, trains, and signalling systems) while private operators run the daily services.

Nationalisation, such as in London and New York, has its benefits. Back in its heyday, the New York subway was seen as an engineering marvel, where many attributed its innovative and efficient system to large amounts of investments — possible only due to government support. Furthermore, governments tend to prioritise societal welfare over profit, ensuring services run even if they are not immediately profitable (e.g. maintaining off-peak and less crowded routes). Without profit-seeking private companies, fare increases can (theoretically) be better regulated to keep public transport affordable. This is especially important in cities with high costs of living.

However, public transport is not necessarily cheaper and of better quality when nationalised. Indeed, problems like commuters hopping over New York metro turnstiles to evade fares and hour-long London Underground delays continue to plague these rail systems. Furthermore, in the absence of market competition in a nationalised model, there is little incentive to push for cost efficiency and operational productivity. Many have argued that while governments are key to establishing a good infrastructural foundation for an efficient subway system, they lack the expertise and profit incentive to manage day-to-day operations well in the long-term.

This explains why Singapore has chosen a hybrid approach, which combines the nimble efficiency of the private sector with the public responsiveness of a nationalised system.

Conclusion

The evolution of the MRT’s financing model reflects Singapore’s ability to adapt to changing demands. In this regard, the NRFF combines the strengths of the private and public sectors. It allows private operators to focus on day-to-day reliability while the Government handles costly infrastructure. This hybrid model avoids the inefficiency of full nationalisation while addressing the challenges of a natural monopoly.

Still, it is not perfect. Shorter licenses may limit innovation, and profit caps could reduce incentives for operators to improve. This approach, however, reflects Singapore’s pragmatism in finding a middle ground to ensure a transport system that works for both commuters and operators. The MRT is more than a mere network of trains; it is a testament to how public policy making can play a role in creating lasting solutions.

This Policy Explainer was written by members of MAJU. MAJU is a ground-up, fully youth-led organisation dedicated to empowering Singaporean youths in policy discourse and co-creation.

By promoting constructive dialogue and serving as a bridge between youths and the Government, we hope to drive the keMAJUan (progress!) of Singapore.

The citations to our Policy Explainers can be found in the PDF appended to this webpage.

.png)

Comments